“Adventure Capitalist: The Ultimate Road Trip” by Jim Rogers

This is part of my re-reading portion of the year. From my previous review:

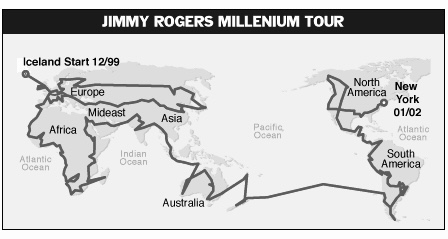

This is one of the best books I’ve ever read. It’s a beautifully written book about the journey of the author, the Indiana Jones of Finance himself, through 116 countries in 3 years, which landed him in the Guinness Book of World Records.

Within the adventurous journey, he encountered the mafias in Russia, nearly died in a blizzard in Iceland and was held captive by rebel soldiers in an African war-zone. An amazing eye-opener book, it also provides us with in-depth analysis on the broad political-economic-and-social condition of each country that he visited. All of this combined with vast knowledge of history, world current affairs and his legendary investment analysis; which inspired me to alter my life to finance, start reading history and follow world current affairs.

I can’t believe that such amazing journey could occur, and so diverse knowledge can be written in a single book. But that’s the beauty of this book, and that’s why it’s number one in my personal chart.

You know that saying you never step in the same river twice, or more relevantly, you never read the same book twice? This is what happened when I read this book for the second time. Please bare with me, this is going to be a very long book review.

The first time I read this book was in 2005 when I was a marketing student aiming to get work at the advertising industry when I graduate. Back then I only read business and self-help books, having no clue about the financial market and what’s history (a subject about old stuffs) got to do with the modern world. But then this book changed my entire worldview.

Through the account of his travels and direct observations on the ground, combined with his deep knowledge on history (Rogers studied history at Yale), his know-how on world politics (he did his masters on Philosophy, Politics, and Economics at Oxford), as well as his legendary analysis on the world market (he was, after all, George Soros’ partner at the Quantum Fund), the book shows the vast world through multiple lenses that go beyond the usual cultural, religious, and tourism perspectives, and through a deeply personal interactions between him and the locals that he met along the way. And on top of all of this, Rogers is an old-fashioned traditional man from Demopolis, Alabama, who was raised by his father with good values and taught to be a gentleman, hence the moral compass he inserted every now and then in his journey.

The book also teaches us about the importance of planning, on taking chances and calculating our odds, on changing course if the original plan goes south real quick, and the risk management plan in case unexpected danger arises, exactly the traits – I later found out – needed to be a successful investor.

But the traits that astonished me the most was Rogers’ real-time knowledge on the market, such as the US Dollar exchange rate when he tried to buy the local currencies, or knows why the price of Timber is dirt cheap in Botswana for such a good quality product, or why he wanted to buy a property in Darwin and Uruguay, why he is reluctant to put his money in Turkey even though it was booming, and many more investment stories as he travelled to the countries in person, including pulling out all of his money from his investments in Argentina after seeing it first-hand the signs that the currency, the economy, and the government are about to collapse (they did, 3 months later). I mean, I thought to myself, who is this guy? And what does he do for a living? Up until then, I was obsessed with the start-up stories of the big companies and their billionaires, I also read almost every entrepreneurial books that I can find, but I have never encountered a person like Jim Rogers before.

This book is actually Rogers’ 2nd book. His first book, Investment Biker, is about his other (crazier) trip around the world: a 2-year trip circling the globe riding a motorcycle, which landed him in the first Guinness Book of World Records (the second is this trip) and earned him the nickname “the Indiana Jones of Finance”, a book I eventually read when I was doing my masters degree in Finance (after ditching the advertising dream), because I wanted to follow his footsteps.

Skip 18 years later, today I’m working in the financial market, and – as Rogers keep advocating in his books and his interviews – I’m now a big reader of history, I follow world current affairs religiously, and whenever I get the chance I travel to weird places and blend in with the locals, taste all the food and adventures myself.

And now that I understand the world a little bit better compared with when I first read this book in 2005, the book is actually even better to read. Because I understand more of all the contexts that he’s talking about, such as the global criminal underworld, the wars happening across the globe, the NGO scams, the weaknesses of the UN, the real function of IMF and World Bank, the troubles at former Soviet satellite states, the hyper-inflations across history, and many more, including more awareness of geography, country-specific issues, all the great places in the world and their stories, the global financial markets, and especially the last chapter which was the most boring part when I first read it, but now turned into the most fascinating conclusion.

But gaining more knowledge in 18 years also means I can now also spot some Austrian school opinions that I grew to disagree with over the years. This is what made me slowly drifted away from following Rogers, where in an interview in the book Inside the House of Money by Steven Drobny Rogers acknowledged the Austrian school label would be most fitting for his views, while since I studied finance, history and politics I have grown to agree more with center-left views (almost the total opposite with Rogers’).

For instance, in the book Rogers partially blamed the global economic collapse of the 1930s on tariffs, quotas and restrictions on trade, while he failed to mention that the Great Depression was caused by loose restrictions (that the Austrian school advocates) in the Roaring Twenties of 1920s, and that the tariffs, quotas and trade restrictions were actually the necessary responding effects to stop the collapse to get even worse.

He also defended the WTO and its predecessor GATT, but didn’t really address the devastating effects they had on countries who had to follow their laissez-faire policies of deregulation, privatization and austerity, regardless of their economic conditions. And nowhere in the book that Rogers tells the story of how Britain and the US really grew from a small nation into a global empire: through tariffs, quota, and trade restrictions, as most clearly described by Cambridge University economist Ha-Joon Chang.

However, re-reading this book provides me with a refreshed perspective on Rogers’ views, that reminds me why he was such an influential figure for me as a young adult and for the way I live my life in general (“obsessed” is a strong word, but I eventually read all of his 6 books, read more books that explain his investment style, read and watch every single interview that he’s made, and even sending him an e-mail to invite him to my wedding – he didn’t respond).

And the way he explains about his [Austrian school] views, kind of make sense if you look at it from his point of view, such as his examples of the tariffs on tomatoes, steel, rice, etc. And to be fair, he did say that World Bank and the IMF have derailed from their original purpose when they were created, something that a hardliner Austrian school would never say. So, in a sense, his views is unique and not rigid towards any ideology despite being close to Austrian School.

Here are some of the best insights from him in this book:

- You have not really been to a country, I believe, until you have had to cross the border physically, had to find food on your own, fuel, a place to sleep, until you have experienced it close to the ground.

- While I have never patronized a prostitute, I know that one can learn more about a country from speaking to the madam of a brothel or a black marketeer than from speaking to a government minister. There is nothing like crossing outlying borders for gaining insights into a country.

- There are about two hundred countries in the world today. Over the next three to five decades, there will be three hundred or four hundred. Many have already begun to disintegrate. The Soviet Union is now fifteen countries. Yugoslavia is now six, Czechoslovakia is now two, Ethiopia two. Somalia? Who knows? Many of us have heard of the Basque independence movement in Spain, but who realized that three other regions of the country—Catalonia, Castilla, and Navarre—also have separatist movements? And along comes East Timor.

- In conjunction with globalization, we are seeing tribalization. While we are dancing to Madonna, drinking Pepsi, and driving Toyotas, people are reaching out for something they can understand and control. The emergence of smaller nations from the ashes of collapsing empires may lead to wars but need not necessarily do so. If borders remain open to trade and migration, we will all be better off.

- Successful investing means getting in early, when things are cheap, when everything is distressed, when everyone is demoralized. On the theory that a rising tide lifts all ships—that even if you are not very smart you are going to do well, if only in spite of yourself.

- One thing I learned from traveling around the world is that when you pull into a large, unfamiliar city, traveling overland, the best and easiest thing to do is to get a taxi to lead you to your hotel.

- In most places around the world, the currency is like a thermometer. It may not tell you what is going on, but it tells you that something is going on, and you know a country is falling apart when even the government will not accept its own currency.

- Take Germany, for example. As long as the economy was expanding, as it did in the 1960s and 1970s, there were no racial problems to speak of. When Germany was expanding, it was open to immigration and people were content. Give us your tired, your poor, your cheap labor yearning to be free, we want them. When Germany became a high-cost place to do business, one of the more expensive economies in the world, and as a result less competitive, the prevailing response was, “Get rid of them. We don’t like those dirty foreigners. It was the Turks who caused our problems.” And along came the skinheads. When jobs were no longer opening up and layoffs were under way, everybody looked for someone to blame. And it is always the foreigners who are blamed: the Christians or the Jews or the Muslims or the white people or the black people or the yellow … the Americans, whoever.

- Later I learned how such state-owned businesses had changed hands with the fall of the Soviet Union. Because nobody owned them—the government had owned them, but now there was no government—whoever had overseen their operation at the time had simply taken possession of them. “It’s mine now,” the manager would say, and there was nobody to stop him. At some point the mafia would come along and say, “Okay, it’s your hotel” or factory or whatever the asset was, but “we are going to provide you with a roof”—insurance, as it were, a hedge against disaster—which was the mob’s way of telling him that he was going to provide them with a payoff. From that point on he would pay extortion money to the mob, and often, because he was incompetent and because the business as a result would fall apart, he and his partners would simply milk the assets until there was nothing left.

- When in Rome, talk to the Romans. That is my variation on the proverb. (Needless to say, I also try to do what they do.) Dining with Namik taught me more about Azerbaijan and the new Central Asia than any guidebook could, and far more than I would ever learn from meeting with a bureaucrat or politician or accepting an audience with a “world leader.”

- I am not the type who would be good at brazenly paying big bribes, wheeling and dealing, giving kickbacks, or anything else. But Namik is. He can deal. He can go to a government official and say, “Okay, what do you need? This is what I need. How do I get it?” That is how the system in the former Soviet Union works. It is not a real system at all. It is not driven by an accumulation of knowledge and capital and expertise. If it is capitalism, it is outlaw capitalism. The entrepreneurs there are not building anything. They are stripping assets. As fast as they can.

- There is a black market in virtually everything that is officially controlled, anywhere. Whether it is wheat, gold, currency, alcohol, or marijuana, somebody is going to figure out a way to get around the restrictions and to capitalize on them. To find out if anything is wrong with a country and how bad it happens to be—to “take the temperature,” as I like to think of it—it is always instructive when visiting a country to visit the local black market.

- Traders are the short-term guys, and some of them are spectacular at it. I am hopeless at it—perhaps the world’s worst trader. I see myself as an investor. I like to buy things and own them forever. And what success I have had in investing has usually come from buying stock that is very cheap or that I think is very cheap. Even if you are wrong, when buying something cheap you are probably not going to lose a lot of money. But buying something simply because it is cheap is not good enough—it could stay cheap forever. You have to see a positive change coming, something that within the next two or three years everybody else will recognize as a positive change.

- The most efficient thing in Russia is the mafia.

- Capital has its own laws as inexorable as those of gravity. Until Russia comes to respect capital, to provide for its safety and nourishment, capital will not come to its aid.

- Raising the specter of war is a technique that leaders have used for centuries all over the world.

- The world managed without passports for thousands of years. Christopher Columbus did not have a passport or a visa. Those great waves of immigrants into the United States in the nineteenth century—those people did not show up at Ellis Island with passports and visas. They just came. Had visas been required, most of our grandparents would have been denied them, and denied entry. Great cities, countries, and cultures grew as people unrestricted by passports and visas headed to the new frontier. This has always been, and is, good for society.

- For many, Africa is a place that you either love or hate in a day or two. I have met people who fly in only to rush to the next flight home. I fell in love with Africa instantly. And I have always loved it, every time.

- I always made a habit of seeking information from several sources. I found that most people in positions of officialdom preferred to give bad information to no information. Rather than admit that they did not know the answer to a question, they would lie.

- Now, how many times have I told people that you should never invest in something unless you yourself know an enormous amount about it? It is a mantra of mine: “No, I am not going to give you any hot tips. The only successful way to invest is to know what you are investing in, and to know it cold. If you do not know about an apple orchard in Washington, do not get into the apple business.”

- Throughout Africa, the former European colonies, imbued with new freedom often bought with oceans of blood, claimed, “We’re going to be democracies, we’re going to have elections, we’re going to create better nations for our people.” It was not long, however, before all those freedom fighters, the great liberators, became dictators themselves. One man, one vote. One time. They liked being in power. They liked the money. They ruined economies, entire societies. Capital fled, people fled.

- On NGO workers: Africans call them the new colonialists. They act the same way. They look upon the countries the same way. They know more than the locals know, and they have better money than the locals. At least the colonialists had to answer to someone. These people have to answer to nobody. They live in compounds with guards and gates and satellite TVs, and they drive around the country telling the poor locals how dumb they are.

- “Coca-Cola,” one of them said, smiling. Which in Tanzania meant “half the price without a receipt.” “Okay,” I said obligingly and handed them 10,000 shillings. The policewomen smiled. I smiled back. “Coca-Cola,” I said, and off we went. The whole thing took less than two minutes. I will say it again: If you are going to Africa, and you want to have the complete African experience, Tanzania is where you will find it.

- Ethiopia is one of the few countries in the world that still uses the Julian calendar, which is named for Julius Caesar and which, in much of the Western world, was supplanted by the Gregorian calendar in the sixteenth century. In Ethiopia, not only was it New Year’s Day, but it was New Year’s Day 1993. Paige and I were each seven years younger the minute we crossed the border.

- What Ethiopia lacks is the incentives to get food to the people who need it. Seeing leaking water towers all over the country, I was reminded that Indian economist Amartya Sen had won a Nobel Prize for demonstrating that most famines are caused not by a lack of food but by government bungling.

- An entire generation of Ethiopians has grown up without learning how to farm. Instead, to put food on the table, they go to town every month, park the donkey, and collect grain. Some recipients, the day we were in Lalibela, carried their ration of wheat directly over to the town market and started selling it. And so, in addition to that generation that has never learned how to farm, there is a generation of farmers who have simply stopped farming because they can no longer sell the fruits of their labor—there is no way to compete with free grain. Africa could feed itself and export food again, but not when its farmers are up against subsidized Western agriculture and free lunches.

- Throughout the continent there are huge markets where one can find bundle upon bundle of T-shirts spread out for sale, donated by places such as the YMCA of Cleveland and the First Baptist Church of Charlotte. These and clothing of all kinds are given as donations in the United States destined for the poor of Africa, but by the time they reach the continent, they are sold as a commercial product. Not only do they enrich the entrepreneurs involved in the traffic, they also put local tailors out of business. The tailors cannot compete, nor can the people who weave cloth, spin yarn, or grow cotton, the people whose costs the tailor incurs.

- There are now something like twenty thousand princes in the royal family. Polygamy is customary, and having numerous children is the norm. (Osama bin Laden’s father had more than fifty children.) And the Saudi government funds all of these princes with six-figure annual salaries.

- The majority of the actual work done in Saudi Arabia is done by foreigners—Pakistanis, Sudanese, Bangladeshis, predominantly Muslims. Accountants, computer technicians, shopkeepers, janitors, and numerous entrepreneurs, all from overseas, constitute a large percentage of the workforce. But a Pakistani cannot just show up in Saudi Arabia and open a butcher shop. He has to find a Saudi partner. The Saudi may never show up at the shop, he may never even see it, but the Pakistani must send him a check every month. Overseas corporations that do business in Saudi Arabia must hire a certain number of Saudis. And while the Saudis may not do much, they nonetheless expect to be promoted to executive positions. Most do very little, if they do anything at all, according to foreign businessmen, and their absentee rate is high.

- I kept marveling at the buildings, infrastructure, palaces, markets, mosques, and life. Someday the oil will be gone or barbarians will arrive, and it will all fade back into the desert. We had repeatedly seen extraordinary civilizations that had inevitably declined and many that had crumbled, even in Europe and Japan. Entire cities in China, Central Asia, and Africa had disappeared over the centuries. The fabled Timbuktu will someday be reduced to ruins resembling those of Carthage. The Arabian Peninsula has always been a sparsely populated wasteland and will be again. What will remain of this in a thousand years? Will archaeologists even be able to find it?

- One basic rule of crossing borders is to get going as fast as possible. Otherwise, someone may change his mind.

- I would submit that the best way to change a country is to engage that country. Isolation rarely brings change. You want to put an end to Fidel Castro’s hold over Cuba? The pope’s visit in the late 1990s did wonders—the Cubans have openly celebrated Christmas ever since, not having done so in more than thirty-five years.

- In the past decade sanctions have become a favorite tool of the United States. Wherever we went, however, we found that they were not effective, because competing products swept in or American products were smuggled in. Either way, American workers, businesses, and taxpayers, not the “offending” countries, were the losers. Sanctions resulted only in more enemies for the United States.

- History is replete with evidence that revolutions do not stem from political suppression as much as aroused expectations that go unmet.

- Plato argued in The Republic that there are four stages in the evolution of nations: from dictatorship to oligarchy to democracy to chaos, and back again.

- Not that I am so clever. Ben Franklin noted that experience is the fool’s best teacher. And I have seen it repeatedly throughout the world: politicians get a country in trouble but swear everything is okay in the face of overwhelming evidence to the contrary.

- In the 1990s, South Americans bought into globalization and opened their economies to the miracles of international trade. But once these were implemented and succeeding, politicians began taking shortcuts to keep themselves in power, borrowing or printing huge amounts of money, leading to disaster. Globalization was not the enemy; it was the corrupt and/or inept execution of globalization that led to the backlash that we saw take root in the streets of Seattle, Genoa, and other cities around the world.

- Never, ever blindly believe that leaders will not act like madmen. History is replete with episodes in which the real patriots were the ones who defied their governments.

- cardinal rule of mine when it comes to investing internationally, especially in emerging markets, is always to have the brokerage account with the largest bank in the country. If the bank gets in trouble, you do not lose everything because the government will take it over. Your shares do not disappear.

- As any student of history knows, many places have had their day in the sun, only to fall into decline.

- I had long wanted to see Potosí for the unique nature of its historic ascendancy, rising out of nothing from a single source of wealth. I had to go to Potosí the way I had to go to Timbuktu. One always learns from history in the flesh.

- You always start small, because you have to make sure everything works. Even with the largest banks—you have to be sure it gets into the right account and that the bank knows what to do with it. I always start small to make sure the mechanics work.

- When I returned home, I realized I had closed as many accounts on this trip as I had opened, in contrast to my previous trip, when I had opened several and closed none.

- In Managua, we were at a filling station refueling when an eight-year-old boy, speaking perfect English, walked over and started going on about the car. His father, who followed him over, introduced himself as the American DEA station chief. It was he who wised us up to the latest in drug-sniffing dogs. Over dinner, regaling us with true tales of high adventure in the world of cops and smugglers—it was one of the most entertaining nights of my life—he explained that the dogs lose their training very quickly. They are not as accurate as most people believe, and all the really good dogs are owned by the drug dealers. The dealers buy the best dogs available; they conceal the dope, put a dog on the case, and if the dog finds the dope, they repack it.

- While in El Salvador, I liquidated the investment I had made in the country during its civil war on my last trip through. Now that there was peace and prosperity—and no longer blood in the streets—I decided to take the profit and move my money elsewhere.

- We had been across enough borders to know that an agitated, belligerent, or simply unhappy customs or immigration official could make an issue out of anything.

- I do not take risks with my money. Ever. The way of the successful investor is normally to do nothing—not until you see money lying there, somewhere over in the corner, and all that is left for you to do is go over and pick it up. That is how you invest. You wait until you see, or find, or stumble upon, or dig up by way of research something you think is a sure thing. Something without much risk. You do not buy unless it is cheap and unless you see positive change coming. In other words, you do not buy except on rare occasions, and there are not going to be many in life where the money is just lying there.

- When Nero took power in Rome in A.D. 54, Roman coins were either pure silver or pure gold. By A.D. 268 silver coins consisted of only 0.02 percent silver, and gold coins had disappeared. Smart Romans had moved their wealth out of the depreciating coinage into investments that maintained their value.

- Everything changes; nothing is permanent, especially one’s portfolio. But all bubbles and manias in the financial markets are the same, and have been throughout history. “New Economy, New Economy!” everyone shouts. Well, we have heard that before. The railroad changed the world. Radio changed the world. The Radio Corporation of America became one of the largest corporations in American history and made gigantic profits. But if you had bought shares in RCA in the late 1920s, you would never have made any money, because the shares never again got as high as they got during the mania. Likewise, if you had bought shares in the railroads in the 1840s and ’50s.

- It may have been Meyer Rothschild, the German banker and patriarch of the legendary House of Rothschild who, when asked how he got so rich, attributed his success to two things. He said he always bought when there was blood in the streets—panic, chaos—when despondency gripped the markets. (In old man Rothschild’s case, investing amid the turbulence of the Napoleonic wars, the blood was just as likely to be literal as it was to be figurative.) And he always sold “too soon.” He did not wait for enthusiasm to peak. He always knew when to get out, and he got out in time with all his money.

- If you learn nothing else in your life, learn not to take your investment advice, or any other advice, from the U.S. government—or any government.

- The largest and most prosperous city at the end of the last millennium was Córdoba, Spain. One of the wealthiest was Seville. Both were more culturally significant at the time than Constantinople, the center of the Byzantine Empire. At the close of the tenth century, the Toltecs, supplanting the great civilization of the Maya, were commencing their two-hundred-year domination of Mesoamerica. What will the world look like a thousand years from now? I have spent five of the past thirteen years driving around the world, and by simply gauging the changes it underwent between the fall of the Berlin Wall and the fall of the World Trade Center, I can assure you that in a thousand years it will be all but unrecognizable. Trying to get an accurate read on things requires a metaphysical stopwatch.

- Sic transit gloria mundi. The glory of the world may pass away, but mankind will prevail.

- I knew instantly when I walked through my door that I wanted to simplify my life. I wanted to clean out the stables of clutter and junk. I wanted never to buy anything again. I became protective of my calendar, which before we left had always been full: a dinner or lunch or a trip or a speech, a project, a party, an interview. I did not want that to happen again. I had gotten along just fine without a calendar for three years. For three years I had made absolutely no entries. But as predictably as the rains in Africa, it threatened to fill up as soon as I was home. If you go back to your old ways, I told myself, if you come home and on day one you end up back where you started, then you probably should not have left in the first place.

I also get reminded why this book has been ranked number 1 in my list for so long: because above all, this is a travel adventure story book filled with surprises, bold acts, and incredible cameos. Such as meeting Iceland’s president Ólafur Ragnar Grímsson, dumping a local currency in a black market in Yugoslavia, encountering belly dancers in Istanbul and Baku, meeting an oligarch in Azerbaijan, got stuck in Uzbekistan when the borders are closed after someone was trying to assassinate the president, eating a snake and turtle in China, eating dog and silk worm in South Korea, eating a horse in Kazakhstan, climbing mount Fuji, became fast friends with a local Russian mafia boss, visiting a Siberian prison, got invited to a lot of strangers’ wedding, running a Russian marathon, getting married at the banks of River Thames London, and visiting a Spanish winery where Magellan went to before he set sail.

In the second part of the book, we would find them crossing the Sahara desert, witnessing African butt dance in an extravagant village wedding near the Senegal-Mali border, visiting the fabled city of Timbuktu, visiting a replica of the St. Peter’s Basilica in the middle of a jungle in Ivory Coast, experienced hyperinflation in Ghana and meeting a local businessman named “God Knows”, visiting a voodoo python temple in Benin, eating porcupine armadillo and wild boar, meeting a prince in Cameroon (no, really, a real prince), eating a boa constrictor in Gabon, entered a war zone in Cabinda, riding a cargo plane out of a war zone and into Luanda where the plane two months later crashed with no survivor, being held hostage overnight by the Angolan army general in their camp, buying a diamond in Namibia said to be worth $70,000 but bought it for $500 and feeling proud of himself but then in Tanzania a diamond merchant said that it was glass, attending a football match in Mozambique, hiking the mount Kilimanjaro, eating crocodile and porcupine in Kenya, getting into the front page of a local Dar es Salaam newspaper, sleeping at a police station in Sudan, and spending Christmas on top of a fisherman’s boat overnight while travelling from Muscat to Karachi.

On the third year of their journey, they went to a horse race and placed some bets in Pakistan, washing their sins in the Ganges during the Kumbh Mela (a Hindu festival that is the largest ever gathering of mankind, with some 60 million people over a few weeks), visiting the Golden Temple of the Sikhs at Amritsar, Taj Mahal in Agra, toured Calcutta’s red-light district led by a group of madams, becoming the first non-locals to drive across the border of India and Myanmar since World War 2, eating kangaroos in Australia, cutting through the middle nothingness part of Australia (from Darwin via Ayers Rock to Adelaide), dining with an Australian MP in Melbourne, chilling in New Zealand Tahiti and Bora-Bora, reaching the southern-most point on Earth: Ushuaia at Tierra del Fuego, visiting what Rogers says as more impressive than any man-made thing he had ever encountered: the Moreno Glacier at Lake Argentino, watching Brazil’s football national team World Cup qualifier match at the stadium, being gloomy on Paraguay as a nation but pleasantly surprised with the development of Bolivia, visiting Potosí (once the largest and most famous city in the Western Hemisphere and the wealthiest city in the world in the middle of 16th century, playing detective in La Paz looking for the person who stole his investment money in Bolivia 10 years ago (and found him and met him in Lima, Peru), looking at the magnificent Panama Canal, eating iguana in Honduras, eating tequila worms in Mexico City.

And the best part of re-reading this book is, I read it during the time when I’m taking a break from serious reading, where I tend to read 2-3 books at once, with the tally of 4-5 books a month and with the annual goal of reading 50 books a year. I’ve reached that number on September, and now I’m taking my time in reading one book at a time. And for this book, I tend to read and stop and google the country and the politics or economic situation that Rogers discussed in 1999-2001, to see whether they have changed in 23 years, such as how’s the Turkish Egyptian and Indian bureaucracies are now, how’s Rogers’ friend Zaza is now doing in Tbilisi, how’s the Central Asian countries are doing now compared with 2 decades ago, how the euro as a currency is performing now, are the Koreans still have special license to sell alcohol in Mauritania, how’s war-torned Angola is doing now, have the series of bureaucracy and corruption in South Africa, Lesotho, Swaziland, Madagascar, Mozambique changed now, how’s the under-reported conflicts in eastern parts of India is doing now, how Thailand, Malaysia and Indonesia are faring now (he went through these countries during the most turbulent times after the Asian Crisis 1997).

After the trip, and after this book, Rogers proceeded to become an even more global super star. But not because of this trip, but because of what he’s best at: investment. He created the Rogers International Commodity Index that puts money where his mouth at, implementing his prediction of a commodity boom that would eventually last more than a decade. And as we can see in this book, he was very well invested already before the commodity index, in the countries that he visited that he thinks were going to benefit greatly from the boom.

Now, do you get it why after reading this book I changed course and pursued life in finance? If you want to understand about the world and can only read one book, read this one.